Have you ever tried to unit test your Query Logic using repositories??

If you do, have you ended writing integration tests instead of unit tests??

Even if you have not tried, you might find this post useful.

I´m going to show you a simple way to unit test your Query Logic. It doesn’t matter what back-end system you are using (relational database, in-memory database, xml file, etc etc etc) nor what ORM tool you are using (EF, NHibernate) as long as you encapsulate the code to interact with these external services using an independent component and that you can defer query execution on your back-end system using an IQueryable object.

In order to do it, we need to write the code in a test-friendly way.

Let´s begin with some concepts and principles related to this problem.

SRP. Single Responsibility Principle. I believe this is the most important principle out there that should be followed. When you break it, you are creating code that is going to be harder to test. There is however one exception to the rule, when you are writing a controller and I don’t mean a MVC controller, I mean the concept used in the more general sense of the controller in Responsibility Driven Design as a Role Stereotype

Dependency injection is a software design pattern that allows a choice of component to be made at run-time rather than compile time

Dependency Injection as specified before is a Design Pattern and DI by itself does not require the use of a IoC container although, it is used with one most of the time but this is not required.

The Law of Demeter (LoD) or Principle of Least Knowledge is a design guideline for developing software, particularly object-oriented programs. In its general form, the LoD is a specific case of loose coupling

- Each unit should have only limited knowledge about other units: only units "closely" related to the current unit.

- Each unit should only talk to its friends; don't talk to strangers.

- Only talk to your immediate friends.

So let’s see how a typical Query repository looks like:

public interface IQueryRepository

{

IQueryable<Movie> GetMovies(string title);

}

public class QueryReprository : IQueryRepository

{

public IQueryable<Movie> GetMovies(string title)

{

var ctx = new MoviesContext();

var movies = ctx.Movies.AsQueryable();

if (!string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(title))

{

movies = movies.Where(x => x.Title.Contains(title));

}

return movies;

}

}

Looks familiar? If you write a repository like this, you won't be able to test your query logic in isolation.

There are basically four problems with this implementation that prevent our code to be unit tested:

We are using the evil anti-test keyword new inside our repository to create the EF context

Using the EF context directly, to retrieve the

IQueryable<Movie>collection to perform the query on it instead of just recieve the collection itselfEven when the

GetMoviesmethod looks extremely simple, it is violating the SRP. This method is doing too much work.

It is creating the EF context

It is getting the

MoviescollectionIt implements the query logic

The

GetMoviesviolates the Law of Demeter, because it’s using directly the EF context, which doesn't actually requires. What we need is to work directly with the movies collection instead

All these problems make impossible to unit test our query logic, if you have repositories like this one, you would have to write integration tests instead.

Refactoring the ugly code

Now let’s refactor this simple code to make it test-friendly.

Removing the new operator

In order to remove the new operator we need to use DI.

First we need to write a custom factory in charge to create the EF context for us. (I wrote a blog about a thread-safe implementation)

This is a simplified version

public interface IContextResolver

{

TContext GetCurrentContext<TContext>() where TContext : DbContext;

void ReleaseContext();

}

public class ContextResolver : IContextResolver

{

private HttpContextBase httpContextBase;

private string connectionString;

private const string ContextPerRequestItemName = "EF_Context_Per_Request_Item_Name";

public ContextResolver(HttpContextBase httpContextBase, string connectionString = "")

{

Condition.Requires(httpContextBase).IsNotNull();

this.httpContextBase = httpContextBase;

this.connectionString = connectionString;

}

public TContext GetCurrentContext<TContext>() where TContext : DbContext

{

var ctx = this.GetContext<TContext>();

if (ctx == null)

{

ctx = this.CreateContext<TContext>();

}

Condition.Ensures(ctx).IsNotNull();

return ctx;

}

public void ReleaseContext()

{

var ctx = this.GetContext<DbContext>();

if (ctx != null)

{

ctx.Dispose();

}

}

private TContext GetContext<TContext>() where TContext : DbContext

{

return this.httpContextBase.Items[ContextPerRequestItemName] as TContext;

}

private TContext CreateContext<TContext>() where TContext : DbContext

{

var ctx = default(TContext);

if (string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(this.connectionString))

{

ctx = (TContext)Activator.CreateInstance(typeof(TContext));

}

else

{

ctx = (TContext)Activator.CreateInstance(typeof(TContext), this.connectionString);

}

this.httpContextBase.Items[ContextPerRequestItemName] = ctx;

Condition.Ensures(ctx).IsNotNull();

return ctx;

}

}

This class is simply acting as a generic factory to instantiate EF Contexts using the Context Per Request pattern

Isolate the EF Context from our repository

This might seem odd at first, but when you clearly identify and separate the responsibilities of each object, your code will become automatically easier to unit-test

So let’s start by identifying what needs to be separated.

The problem in the last code sample is that the repository communicates directly with the EF context to retrieve the IQueryable collection of objects in order to create the query.

What we really need is the collection of objects to work on

Since the IQueryable interface is capable of execute deferred queries, it’s perfect to expose the initial collection of objects to perform the query.

So let’s add the following objects

public interface IMoviesDataProvider

{

IQueryable<Movie> GetMoviess();

}

This simple interface will be in charge to provide the initial objects as an IQueryable collection to perform the query

public class MoviesDataProvider : IMoviesDataProvider

{

private IContextResolver contextResolver;

public MoviesDataProvider(IContextResolver contextResolver)

{

this.contextResolver = contextResolver;

}

public IQueryable<Movie> GetMoviess()

{

var context = this.contextResolver.GetCurrentContext<MoviesContext>();

var items = context.Movies.AsQueryable();

Condition.Ensures(items).IsNotNull();

return items;

}

}

Notice how the implementation has become really simple. This implementation will be in charge to communicate directly to the backend system to expose the data as an IQueryable collection. Since this object will talk directly with the database using EF, we use DI to pass a reference to the IContextResolver object (remember, this object will be in charge to get the correct instance of the EF context using the Context per Request Pattern)

Implement the Query Logic

The next step is to implement your query logic in your repository object.

This is quite simple since now we have identified and isolated single responsibilities in several objects.

So let’s refactor our repository code:

public class MoviesRepository : IMoviesRepository

{

private IMoviesDataProvider moviesDataProvider;

public MoviesRepository(

IMoviesDataProvider moviesDataProvider)

{

this.moviesDataProvider = moviesDataProvider;

}

public QueryResults<Movie> FilterMoviesByTitle(string title, PagingInfo pagingInfo = null)

{

var movies = this.moviesDataProvider.GetMoviess();

if (!string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(title))

{

movies = movies.Where(x => x.Title.Contains(title));

}

return QueryResults.Of(movies.ToList(), movies.Count());

}

}

public interface IMoviesRepository

{

QueryResults FilterMoviesByTitle(string title, PagingInfo pagingInfo = null);

}

There are several things to note on this simple code:

The repository no longer depends on the EF Context, now it depends on the

IMoviesDataProviderinterface which can now be easily mocked to return a dummy in-memory collection to work on when unit testing.The Query Logic is being encapsulated in this layer

The result of the query is an in-memory object

IList(which is wrapped in theQueryResultsobject) which means that at this point the query is being executed on the server.Since the query has been executed at this point, we can safely return in-memory objects represented by the

IListcollection

Some people would argue about the use of the IList instead of returning an IQueryable.

With an IQueryable you get more flexibility since you can actually keep modifying the query all the way until the GUI, but in essence, that’s the problem. Since the query will be spread out across the application, there’s no way to test it in isolation.

For more info about IQueryable

Here is the code of the QueryResults and PagingInfo objects:

public sealed class QueryResults

{

public static QueryResults<TTarget> Of<TTarget>(IList<TTarget> results, int virtualRowsCount)

{

Condition.Requires(results).IsNotNull();

Condition.Requires(virtualRowsCount).IsGreaterOrEqual(0);

return new QueryResults<TTarget>(results, virtualRowsCount);

}

}

public class QueryResults<TTarget>

{

public QueryResults(IList<TTarget> results, int virtualRowsCount)

{

Condition.Requires(results).IsNotNull();

Condition.Requires(virtualRowsCount).IsGreaterOrEqual(0);

this.VirtualRowsCount = virtualRowsCount;

this.Results = results;

}

public int VirtualRowsCount { get; protected set; }

public IList<TTarget> Results { get; protected set; }

}

public sealed class PagingInfo

{

public PagingInfo(

int page = 1,

int pageSize = 10,

string orderByField = "",

OrderDirection orderDirection = DataLayer.OrderDirection.Ascending)

{

Condition.Requires(page).IsGreaterOrEqual(1);

Condition.Requires(pageSize).IsGreaterOrEqual(1);;

this.Page = page;

this.PageSize = pageSize;

this.OrderByField = orderByField;

this.OrderDirection = orderDirection;

}

public int Page { get; private set; }

public int PageSize { get; private set; }

public string OrderByField { get; private set; }

public OrderDirection OrderDirection { get; private set; }

}

These objects are simple DTO’s

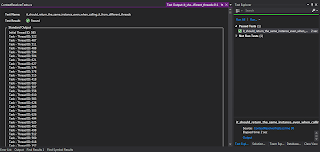

Writing the Unit Tests

Finally we can have fun writing our unit tests:

[TestClass]

public class MoviesRepositoryTests

{

[TestClass]

public class TheFilterByTitleMethod

{

[TestMethod]

public void it_should_not_apply_a_filter_when_the_title_is_empty()

{

var fixture = new Fixture().Customize(new AutoMoqCustomization());

var moviesDataProviderMock = fixture.Freeze<Mock<IMoviesDataProvider>>();

var movies = Builder<Movie>.CreateListOfSize(10).Build().AsQueryable();

moviesDataProviderMock.Setup(x => x.GetMoviess()).Returns(movies);

var sut = fixture.CreateAnonymous<MoviesRepository>();

sut.Should().NotBeNull();

var res = sut.FilterMoviesByTitle(string.Empty, null);

res.Should().NotBeNull();

res.VirtualRowsCount.Should().Be(10);

res.Results.Should().NotBeNull().And.NotBeEmpty().And.NotContainNulls()

.And.OnlyHaveUniqueItems().And.ContainInOrder(movies);

}

[TestMethod]

public void it_should_apply_the_filter_when_the_title_parameter_is_not_null()

{

var fixture = new Fixture().Customize(new AutoMoqCustomization());

var moviesDataProviderMock = fixture.Freeze<Mock<IMoviesDataProvider>>();

var numberOfElements = 10;

var numberOfMatchingTitles = 3;

var title = "Testing";

var movies = Builder<Movie>.CreateListOfSize(numberOfElements)

.TheFirst(numberOfMatchingTitles)

.With(x => x.Title, title)

.Build().AsQueryable();

var matchingMovies = movies.Where(x => x.Title.Contains(title));

moviesDataProviderMock.Setup(x => x.GetMoviess()).Returns(movies);

var sut = fixture.CreateAnonymous<MoviesRepository>();

var res = sut.FilterMoviesByTitle(title);

res.Should().NotBeNull();

res.VirtualRowsCount.Should().Be(numberOfMatchingTitles);

res.Results.Should().NotBeNull().And.NotBeEmpty().And.NotContainNulls()

.And.OnlyHaveUniqueItems().And.ContainInOrder(matchingMovies);

res.Results.Count.Should().Be(numberOfMatchingTitles);

}

}

}

Have fun!